Chartham Paper Mill – Traditions and Tracings

Welcome to Chartham Mill, where forward thinking and positive progress went hand in hand with a heritage of well over 250 years of papermaking. For more history and images of Chartham paper Mill Click this link

Chartham Village

Lying in charming rural surroundings, just two miles from the historic city of Canterbury, the pleasant Kent village of Chartham, with a population of just over 3,500 people, has long been a thriving industrial community. Records, in fact, trace the history of ‘Certaham’ as it was once called, as far back as the 11th century. Chartham Mill probably began its career grinding corn, but with the growth of England’s weaving industry, it became a ‘fulling mill’ where woven cloth was softened and smoothed. Thus, although it was not converted for papermaking until 1730, it is probable that Chartham Mill, in one form or another, has always been the industrial hub of the community.

Its delightful situation on the River Stour is an almost perfect one, both environmentally and from a papermaking point of view – two facts which did not escape the attention of one time owner Mr. John Howard and his mill manager Mr. Harry Cremer. They, according to a report which appeared in The Stationery World of 1907, must have been well ahead of their time in terms of staff relations and working conditions. It was observed “Papermaking is usually a somewhat prosaic pursuit, but if it is possible to make the best of the sylvan surroundings and to introduce into the paper industry a tone of brightness and refinement, it is here to be found, and Mr. John Howard the sole proprietor and his manager, Mr. Harry Cremer are very strong believers that if good order, cleanliness and a right sense of responsibility is to be inculcated into the minds of the work people, this can certainly be encouraged by environments such as exist both at the Chartham Mills and at the Canterbury Departments”.

This extensive and appreciative article went on to comment that “Paper, and paper of a very high class, has been made by the Chartham Mills since very early in the 18th century” . And perhaps the visitor may be interested in a short trip back into the early 1700s; to the origins of a paper mill and the beginning of an unfailing reputation for quality and care which has never been sacrificed despite disasters, wars, and twentieth century progress.

Origins of a Paper Mill

Chartham was transformed into a two-vat paper mill around the year 1730 by Peter Archer, and we have an excellent description of its fixtures and fittings carried by the ‘General Evening Post’ dated ‘from Thursday, May 18th to Saturday, May 20th of 1738’ which advertised:

“Immediately To Be Sold A very good new-built paper mill, situate and being in the Parish of Chartham, where there is plenty of water, two miles distant from the City of Canterbury, built by Peter Archer, lately deceased, containing two engines, two vats and all other utensils and conveniences necessary for the making of paper, together with a very good dwelling house adjoining the said mill”.

As so frequently happened with such undertakings, the mill changed hands many times over the ensuing 60 years, taking its toll on the pockets of its various leaseholders and owners. It was apparently rebuilt in 1795 and was finally acquired by William Weatherley around the end of the 18th century, complete with “waterwheels, gears, engines, pumps, and other utensils, collection of rags, 16 acres of rich meadow land and the cottages next to the church yard”. And here began Chartham’s success, the mill staying in the Weatherley family for more than 60 years, during which time it passed to Weatherley’s brother. Between the years of 1849 and 1851, Weatherley modernised the mill and introduced the first papermaking machine, which was put down by Bryan Donkin.

By 1857 the younger William Weatherley, nephew of the original owner was taking an active interest in the mill with his business partner, Mr. C. T. Drew. Weatherley was a brilliant young man, full of ideas and ambition. It was his innovation to introduce straw with rags in the papermaking process and, although it is thought to be this department which caused the disastrous fire of 1857 which completely razed the mill, Weatherley turned even this to good advantage by taking the opportunity to put his revolutionary ideas of ‘the perfect mill’ into practice.

The Weatherley Revolution

William Weatherley was typical of his kind. A man prepared to risk his personal fortune to realise a dream of perfection. Some of his ideas were lavish almost to the point of foolishness if viewed in a strictly commercial light and yet, in principle, they were correct and in practice they proved effective and worthwhile.

He began by diverting the watercourse, at vast expense but ‘to ideal effect’. This action probably made a tremendous difference to the capacity of the mill which, around the early 1850s, had a maximum weekly output of something like 4 or 5 tons of ‘good ledger paper’, made with the aid of the power produced by two primitive water wheels.

Next on Weatherley’s list was the installation of Chartham’s first air drier – incidentally the first air drier in the whole paper industry – at a cost of £8,000. By 1860 production was raised to 8 tons of high quality rag paper each week.

Weatherley’s final expenditure was on The Grange : the beautiful house surrounded by landscape gardens and lawns leading down to the water’s edge. From here he could keep a watchful eye upon the progress of his brain child and quietly survey the scene of his success – but not for long. Weatherley’s money had run out; to good effect for the future of the mill, but not to his personal advantage. In 1862, a limited company of creditors was formed and they continued to run the mill, with varying degrees of success, under Weatherley’s supervision. But time, too, was running out for Weatherley – and a new beginning was on the horizon for Chartham Mill. In 1871 it was to be adopted by a new owner and his mill manager who, between them, were to take the Mill, its products and reputation to greater heights of success and into the brave new world of the twentieth century. This was a world of unsettled peacetime punctuated by two world wars; a world, too, of progress and development; a world in which a simple error by a beaterman led to the successful manufacture of Chartham’s first Tracing Paper.

The Howard Regime

In the year 1871, traveller, businessman, Justice of the Peace and one time Member of Parliament for Faversham, Mr. William Howard, acquired Chartham Paper Mill as a going concern. Historical conjectures suggest that Howard looked upon Chartham as a hobby rather than with a view to serious commercial work – a seemingly unjust statement in the light of the tremendous advances his investment and concern precipitated. A man of means, Howard made sufficient improvements to increase an output of around 7 or 8 tons per week to an impressive 20 tons; government work accounting for much of this increased output during the 1880s. John Howard took over the mill from his late father in 1888 and he, too, was a dedicated man with an obvious love of his business and the people involved in it. It was under the Howard name that Chartham Mill was to be known until the most recent years, even after its purchase by Wiggins Teape.

At the turn of the century, even though Chartham already had the highest reputation in the whole of England as manufacturers of banks, loans, writing and account book papers and pastings, the mill’s output was nominally lowered in order to achieve an allround improvement in quality. At the time it was noted that, although modern machines “are speeded to bordering on 600ft per minute, the fine old machine at Chartham never runs at a speed over 55ft per minute”; and for thick loans, 23ft per minute was the average. The mill had been brought up to date with two turbines, new boilers, two wells yielding 600 gallons per minute, and a complete overhaul of the papermaking machine. And yet, with all this mechanisation and modernisation, the spirit of craftsmanship was evident. Again, The Stationery World describes what we would now call qua I ity control: “it is positively refreshing to observe the scrupulous care evidenced in every operation and to note how, when the finished article is dealt with, trained hands carefully examine each sheet with a minuteness and care which means that only absolutely perfect paper is passed”. Today, at Chartham, methods have changed, but that basic principle remains.

A New Era, a New Product

During the 1930s, Chartham became part of the Wiggins Teape Group but remained in the charge of the then Director and Mill Manager, Mr. Harry Cremer. It was his foresight which transformed a mistake by a Beaterman in overloading his beater with vegetable starch and thus producing a translucent paper, into the basis of Chartham’s future fame as a producer of fine tracing. During the thirties, though, Britain was still iotally dependant upon imported Tracings and in 1934, experiments were begun at Chartham to produce a translucent paper of sufficient quality to satisfy Britain’s home requirements . Such a paper was eventually produced in 1939 and was destined to carry the original plans of nearly all machinery and munitions developed in Britain between 1939 and 1945. At the end of the war, pl ans to re bu i Id and re-equip Chartham exclusively for the production of an improved product – Gateway Natural Tracing -were put into action . Research began to test the viability of producing Tracing from all-wood fibres and experiments were undertaken to determine the most suitable raw materials and the best possible equipment on which to produce such a high quality product. By 1948 Wiggins Teape had all the answers and reconstruction work could begin to prepare the mill for manufacture of Gateway Natural Tracing. In 1949 Chartham No. 1 machine was installed and operative, replacing the 98 year old veteran machine. Almost from the first day, modifications were being made to No. 1; improving its production potential and making this one of the most highly instrumented and controlled papermaking machines in the country. Sales of Gateway Natural Tracing rocketed , both at home and abroad and by 1962, a second machine was operational , doubling the mill’s capacity. Gateway Natural Tracing was continually improved ; production and control methods were constantly updated until, in 1966, came the ultimate control: computerisation. Finally 1972 saw the introduction of No. 3 machine which has a capacity almost as great as the combined output of 1 and 2 machines.

Production on No. 3 Machine

In November 1972, Chartham’s No. 3 machine was inaugurated. Then Europe’s largest and most modern machine for the production of Natural Tracing paper, the project cost £3 million and virtually doubled the mill’s capacity. No. 3 machine incorporates many sophisticated mechanisms, all necessary to ensure that every sheet of Gateway Natural Tracing is of a consistent qua I ity. The papermaking process begins when the heavily beaten cellulose fibres, suspended in water, are piped from the refiners into the head box of the machine at what is known as the ‘wet end’ (plate 1). The fibres are evenly distributed across the width of a continuous wire mesh. As the mesh moves, water drains rapidly away, leaving a layer of wet interlocking fibres -the paper web. To assist formation of the web, more water is removed with the aid of a series of table rolls and foils and, subsequently, by a bank of suction boxes (plate 2). At this early stage, the paper is sti II very weak and its edges can be trimmed neatly and precisely by a fine jet of water. The waste paper falls into the hog pit below the mesh and is eventually recycled. The water which is drained out of the paper is also recycled – a very necessary procedure as it takes 100 gallons of water to produce 1 tonne of paper. When it reaches the end of the first stage, the paper is still mostly water but is strong enough to support itself whilst crossing to the Press Section of the machine. Here it is carried by continuous felt blankets through a series of four presses (plate 3) which squeeze out more water to consolidate the web.

As the paper leaves the last of the presses, it becomes entirely self supporting and moves on through banks of steam heated, metal drying cylinders. Drying occurs, at this stage, through a process of evaporation, as opposed to squeezing, and the temperature of the cylinders is carefully controlled by a valve (plate 4). Total contact with the drying cylinders is ensured by pressure from continuous fabric blankets. This stage of the drying process is responsible for Gateway Natural Tracing’s excellent flatness and helps to prevent waving and curling of the paper. Pressure rolls iron out the surface coarseness of the paper to the correct degree to achieve a smooth or matt surface finish, as required. The semi-dried paper passes on through a size bath; this contributes to the finished paper’s excellent drawing surface and flexibility. Next a series of after driers (plate 5) dry the paper further until its moisture content is perfectly adjusted (in equilibrium with a relative humidity of 55-60%). Once the paper has been formed and dried, the scanning head of the Substance and Moisture Gauge (Plate 6), examines it before reel-up. The scanner feeds information on grammage and moisture content into the computer which controls the papermaking process all the way down the line and continually makes adjustments so that the paper meets the specifications required for the making.

Computer Control at Chartham

Gateway Natural Tracing is strictly controlled throughout every stage of production , all the way from the preparation of the raw materials to reel-up. The stock is refined at a constant power level and leaves the refiners as a consistent material. This earliest process is a very vital one because the stock must be refined to precisely the correct level to produce the required transparency in the finished paper. Correct refinement ensures that a steady and consistent flow of stock passes onto the papermaking machine.

Once the stock is fed onto the machine, as we have already seen, sophisticated regulators control the many possible variables so that every stage of the process is efficiently measured, and the paper conforms to optimum standards. Computer control of the papermaking process was pioneered at Chartham during the early 60s and the present computer, although much advanced in comparison to the original model, is based on some of those early results . Computer control is of most value at the ‘wet end ‘ of the machine which is notoriously the most difficult to control in every papermaking process . Before the advent of the computer, much depended upon the experience of the machine minder and his ability to assess the need to vary machine speed in order to maintain a correct substance (weight) according to the variations in consistency of the stock flowing onto the machine.

With the aid of the computer, a mechanical model maintains wet end conditions at a constant level , automatically taking account of, and correcting the principal variables. As a result, the paper machine can run faster and is capable of a larger and more consistent output of Gateway Natural Tracing Paper. Once the paper reaches Quality Control, samples are tested under laboratory conditions for substance, thickness, colour (shade), finish, tear strength, smoothness, moisture content and other essential technical characteristics. By carrying out so many tests, Wiggins Teape can be sure that every sheet of Gateway Natural Tracing in any one substance will have the same look, feel and technical properties as every other sheet in that substance. Even cutting and packing are carried out under controlled conditions before Gateway Natural Tracing Paper begins its journey to one of the 80 countries to which it is currently exported.

The Products of Chartham Mill

Gateway Natural Tracing Chartham’s most famous product, Gateway Natural Tracing is made from pure cellulose fibres and water. Its most vital ingredient, though, is technical skill. Substance, grammage, transparency to ultra-violet light and moisture content are all regulated by Chartham’s advanced computer technology. And it is this technology, too, which ensures that Gateway Natural Tracing retains its long standing reputation amongst designers and draughtsmen throughout the world. Simulator Primarily a publishing paper, Simulator is produced with the same care and attention to detail devoted to Gateway Natural Tracing. Simulator has a good printing surface for all conventional processes and, used as a special effects paper, it is ideal for book jackets, overlays, diagrams, inserts and leaflets.

Coating bases for Diazo Intermediates Coating bases require the same constant quality and care in manufacture as Gateway Natural Tracing Paper and, again, Chartham’s technological advances are essential to correct, consistent production. Transparent Sensitizing Base is hard sized to limit the penetration of Diazo coating substances and must be free of any chemicals which could react with the Diazo. Conversely, the correct acid balance must be achieved to provide a suitable environment for the Diazo compounds. Transparent Lacquering Base contains no acid and is not sized; it is designed to be lacquered on both sides prior to Diazo coating. One-sided Transparent Lacquering Base is designed to be lacquered on one side only.

Looking Ahead Chartham Mill

is part of the Wiggins Teape Group and so has the backing of an experienced marketing organisation with a world-wide system of branches and agents to feed back information on changing requirements. With the aid of this vast intelligence network, Chartham Mill is able to remain constantly abreast of new developments which are, if worthwhile, incorporated into its own research programme. Yet, alongside this continued determination to develop and progress, Chartham Mill also continues the traditions of personal and environmental consideration which have encouraged contentment and craftsmanship over more than two centuries. To the reader of this brief story of Chartham Mill, the following quote from an issue of ‘Paper’ (December 1972) after the inauguration of No. 3 machine, will sound almost familiar: ” … there was an inevitable conflict between rural amenity on the one hand and industry on the other, between the provision of jobs and the provision of peace and quiet … Wiggins Teape have done a great job in mitigating the impact of the one on the other. Chartham may not be a new Jerusalem, but it is certainly not a dark satanic mill and it is pleasant to think that there are not only more jobs here than ever before but, as a result of a great deal of work in building a mound and planting it with trees, putting in culverts for flood prevention and minimising noise, the environment here is as good as it ever was in living memory.”

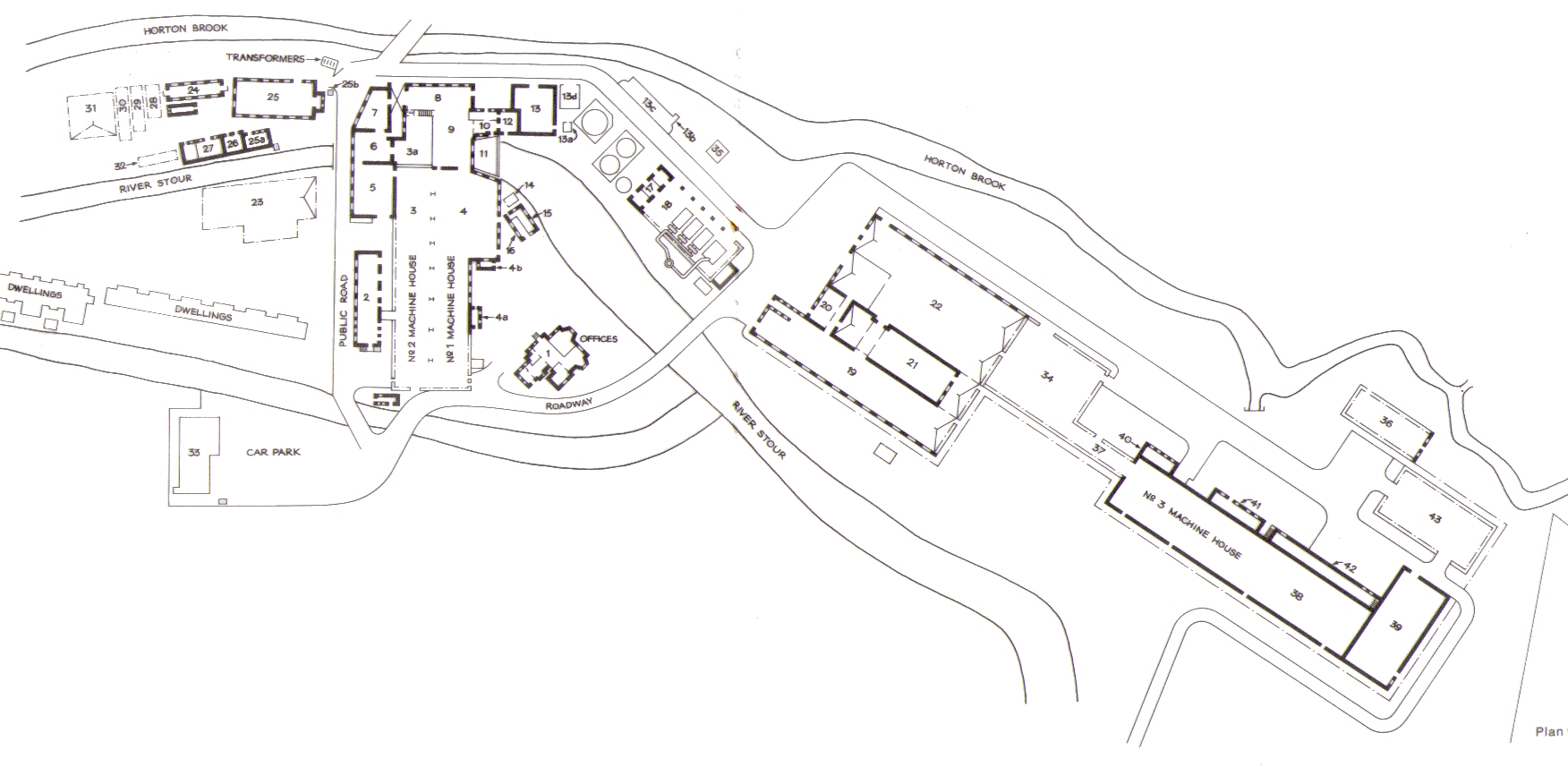

GUIDE TO CHARTHAM

| 1 The Grange 2 Instrument Block & Offices Nos 1 & 2 Machine Houses No 1 Annexe No 1 Basement 3 Mezzanine Floor Area 4a 4b Compressor & Vent Rooms 5 Fitters Shop 6 Engineers Stores 7 Carpenters Shop 8 & 9 Pulp Store & Beater Floor (1st floor) Broke Store & Drop Chest (Ground floor) 10 Water Tank Room (2nd floor) Beater Room Annexe (1st floor) Diesel Room Sub Station (Ground floor) 11 Vent Room Old ‘Allen ‘ Room 12 Old Boiler House 13, 13a Effluent Pump House 14 Fire Pump House 15 & 16 Garage & Sprinkler House 17 & 18 Boiler House & Water Treatment 19 – 22 Finishing Department Finishing Extensions (1969) 23 Pulp Store | 24 Canteen 24a Lorry Garage 25 Laboratory 25a, 26, 27 OiI Store, Old Stables etc. 28 Canteen Store, Timber Store 29 Builder’s Store 30 Metal Store 31 Lower Yard Store 32 Wind Tunnel 33 Social Club 34 Warehouse 35 Sauna Building 36 New Office Block 37 Passageway between Warehouse & No. 3 Machine House 38 No. 3 Machine House 39 Stock Preparation Room 40 Toilets & Cloakrooms 41 Engineers Workshops, etc. 42 Papermakers Offices, etc. 43 Pulp Store |